The Referendum Party (1997)

The story of one man's ambitious attempt to change British politics forever.

If you say ‘British Politics’ and ‘1997’ to almost anyone, you will probably hear the name ‘Tony Blair’ shortly afterwards. From the Granita pact to Blairites, Blairism and Blair’s Babes1, Anthony Charles Lynton Blair looms large over the period. Many have written wonderful and interesting things about how things could only get better under New Labour but there is a very different but equally important story hidden behind the Blair behemoth, called The Referendum Party.

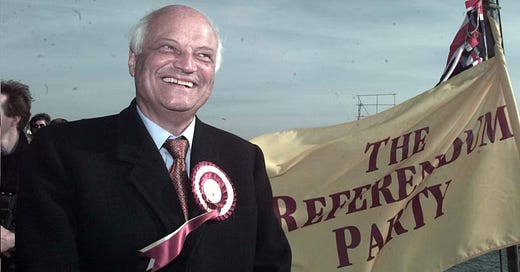

James Goldsmith

The Referendum Party was the brainchild of James Goldsmith, who is such an interesting character that to truly tell this story properly, we will have to get to know him much better. Goldsmith was part of a group of modern financiers who completely transformed the landscape of British business by leading hostile takeovers of publicly listed companies from the early 1960s. He was in other words, one of Britain’s first corporate raiders and asset strippers, focused on finding companies he could buy majority positions in on the London Stock Exchange, before voting through board changes that enabled him to shut down facilities, sell off parts, cut staff and reduce costs.

All this was done in a concerted attempt to convince ‘the market’ that the company was healthier than ever, thus driving the share price up. Knowing this was more illusion than reality, once the share price was up a good amount, Goldsmith would then divest at least a large proportion of his position, realising the gains and generating seriously big personal profits in almost no time at all. He got this methodology down to a fine, brutal art, and specialised particularly in food and drink brands, which he then re-organised under his own company name Cavenham Foods.

At the time, much of Britain’s food and drink sector was inherently regional and much more fragmented than now2. In the 1960’s, due to transport costs, lack of logistical technology and challenges over storing perishable goods, every region, town and city had its own brands with only a few of the biggest brands truly available nationwide. Goldsmith started out going after small regional bakeries and retailers like the newsagent group McColl’s, as well as popular brands including Carr’s biscuits (Carlisle), Holland’s toffee (Southport) and Carson’s chocolate (Bristol).

In 1971, Goldsmith crossed the Rubicon by selling a big chunk of his still relatively small Cavenham Foods empire to fund an ambitious bid for Bovril. It was an extremely famous British company that didn’t just own it’s eponymous product, but other big-hitters including Marmite and Ambrosia, plus a large number of dairy farms that produced the ingredients used in making them. Like many companies of the time, Bovril was still owned by a founding family, which was now into it’s third generation3 and it was in many ways, a true British institution.

When Goldsmith’s attempt at a hostile takeover of Bovril became public knowledge, he was condemned by the financial press, employees and the company owners. But despite these widespread concerns the company was publicly listed, and they couldn’t stop him from being ultimately successful in buying up enough shares to take a majority position. Over the next few years, he then sold off so many parts of the Bovril empire (and using the proceeds to line his personal pockets) that he ended up getting every penny of his original £13 million investment back, without diluting his shareholding at all. The deal was also transformational for Cavenham Foods and by 1974 it was the third biggest food business in Europe behind Nestle and Unilever.

In 1976, Goldsmith received a Knighthood in the ‘Resignation Honours List’ of Harold Wilson. This was the infamous ‘Lavender List’ which proved incredibly controversial due to containing a number of wealthy businessmen, including Goldsmith, who had no connection to the Labour Party. Indeed, many within the Labour Party had spent the best part of a decade decrying the ‘smash, trash, burn and churn’ tactics of people like Goldsmith, who cared very little about the impact of their ‘business decisions’ on real people and certainly never stopped to think about whether it was morally right to impose swingeing cuts to profitable businesses, that would then condemn local communities to years of high unemployment.

At the same time, Britain was having serious economic struggles with stagflation, and infamously had to ask the IMF for a loan during the Sterling Crisis. This backdrop, finally smashed apart the slowly decaying myth that Goldsmith and his fellow financiers had helped Britain build a strong, resilient modern economy. Combined with the Lavender List controversy, ‘open season’ on Goldsmith was effectively declared and in 1977, an episode of the BBC’s ‘The Money Programme’ directly called out his corporate raider methods and management practices at Cavenham on primetime television. Goldsmith, incensed, appeared on a follow-up programme the next week and in a robust and combative defence, he showed that he desperately wanted to be seen as a ‘creator’ and not a destroyer, and despised being portrayed as a ‘buyer and seller’ of businesses. He also took severe umbrage with having himself or anything he was associated with described as a ‘failure’.

In the end, it all proved too much and Goldsmith, incensed that the ‘political and media elites’ had turned on him, moved to the United States shortly afterwards. He abandoned his goal of making Cavenham a global food giant and slowly started dismantling it piece by piece and pocketing the proceeds. Bovril was sold in 1980 to Beecham’s for £42million, the same year Goldsmith officially ceased to be Cavenham Foods chairman. He continued to dabble in various money-making schemes in North and South America throughout the 1980s, before announcing his retirement and a move to Mexico in 1987, aged 54.

The Referendum Party

And that, perhaps, should have been that. But then The Maastricht Treaty happened. Maastricht is not the genesis moment for British exceptionalism, euro-scepticism and Brexit, but it’s probably the most significant staging post of the entire journey. It’s ascension into UK law nearly toppled a Conservative government that had only just won the 1992 election, and culminated in John Major infamously describing three of his cabinet members as ‘bastards’ in a TV interview. Combined with the indignation of Black Wednesday, triggered by the UK’s exit from the ERM4, 1992 was the year that European fractures and fault lines that would never heal, formally erupted in full view. However, despite all of the controversy and various amounts of internal disagreement, the official Party lines of the Conservatives, Labour and Liberal Democrats between 1992 and 1997 were to support Maastricht and further European integration and to have an open mind about future currency union. Always one for exploiting an opportunity, this situation provided Goldsmith with one he couldn’t resist.

Goldsmith’s views on Europe were pretty one-dimensional. He loved Europe; he was born in Paris in 1933, staying there until being forced to flee Nazi Blitzkrieg in 1940, and he held dual Anglo-French citizenship for his entire adult life. For Goldsmith, perhaps still scarred by those events, the EU was a political vehicle to enable Germany to dominate Europe politically and he regularly painted the German Chancellor Helmut Kohl as the nefarious architect of a new European order. He also had a strong distaste for some of it’s free trade principles, particularly as the removal of some long-standing economic protections and tariffs would expose some of his businesses to increased competition.

In 1993, Goldsmith gave a televised lecture on Channel 4, which was also published in the Times, which he titled ‘Creating a Superstate is the way to Destroy Europe’. The piece is littered with now familiar sounding comments about ‘sovereignty’, the ‘signing away rights to bureaucrats and politicians British people didn’t vote for’ and the use of the word ‘Brussels’ as a de-facto slur. A year later, emboldened by the reaction his opinions generated, Goldsmith sent a shockwave through British politics by launching The Referendum Party and it’s one and only policy; to hold a referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU. The Party was entirely financed directly by Goldsmith, and was structured in such a way that he had complete control over it; it was impossible for anyone to become a Party member.

The Referendum Party generated some real interest from the media and the public, particularly over it’s claim that if it achieved it’s goal of securing a Referendum, it would disband itself. This enabled a number of euro-sceptic Conservatives to tacitly endorse the party, under the cover that it wasn’t a ‘real rival’ with a desire to govern the country. Confusingly, at the same time, The Referendum Party claimed to not be a euro-sceptic Party at all, and was in fact ‘agnostic’ towards Europe, with it’s only true belief being that British voters should have ‘a say’ in the matter. This was more smoke and mirrors than reality, designed to give the party the broadest appeal possible across the electorate.

The 1997 General Election

In 1995, and with the next election looming, The Referendum Party started to get themselves properly organised. Hundreds of staff were employed at a new HQ in London, plus regional and consistency offices were set-up, and hundreds of parliamentary candidates recruited and trained. One of the biggest tasks during this quick burst of professionalisation was setting up the Press Office, control of which was given to a young but formidable woman, with the right mix of Conservative and euro-sceptic political instincts. Her name was Priti Patel.

One of her key duties was creating the Party’s newspaper, which she snappily titled ‘News from The Referendum Party’. The first issue in February 1996 led with the front page title ‘They Lied Through Their Teeth’ and was distributed to 24 million UK households, at a cost of £2million. It marked the start of a quite incredible spending spree, with Goldsmith publicly committing he would invest at least £20million of his own money in the run-up to the election and Referendum Party advertisements started appearing in all major national newspapers as well as cinemas. Overall, they spent three times as much as the Conservatives and five times as much as Labour on press adverts alone.

Goldsmith also aggressively lobbied the Party Election Broadcast (PEB) to allow the Referendum Party to have more than just the one Party Political Broadcast slot that any Party fielding more than 50 candidates receives automatically, arguing that his levels of spending and the subsequent profile boost for the Party should entitle them to at least three. After taking the PEB all the way to the High Court of Justice with no success, Goldsmith went on Radio 4’s Today program to label the BBC as ‘The Brussels News Corporation’ and started making plans to record his own additional party broadcast anyway, put it on 5 million branded VHS video tapes and to then post them directly to voter’s homes in the run-up to the election. This was both seriously expensive and incredibly innovative, being the first ever use of directly distributed multimedia content in UK politics. Despite being an entirely offline affair, the 12-minute video even had a click-bait title; ‘The Most Important Video You’ll Ever Watch’, and a call to action of ‘If You Care About Britain, Please Pass This Video On’.

The Referendum Party stood 547 candidates in the 659 UK consistencies, more than any minor party had ever fielded before. It did not stand in constituencies where the Tory candidate was a prominent euro-sceptic. This, like everything else, was only made possible through Goldsmith’s huge levels of financial investment. The Party went into the election on a high; it’s October 1996 Party Conference in Brighton saw 5,000 attendees, and speeches from not just Goldsmith, but also the ecologist David Bellamy, ex-Speaker of the House of Commons George Thomas, and the actor Edward Fox. Ironically, the latter’s son Laurence, would follow a similar path to demagoguery as Goldsmith, and officially launched his own anti-establishment political party, Reclaim, in 2020.

Further adding to the momentum, just a few months before the election George Gardiner, the Tory MP for Reigate, defected to the Party, giving them their first MP in the House of Commons. Meanwhile, The Daily Mail, The Daily Telegraph and The Times all wrote supportive by-lines, whilst Goldsmith was the subject of a significant feature in Vanity Fair’s May 1997 edition. On April 9th 1997, the Party launched it’s election campaign in Newlyn, Cornwall where it was able to tap into local concerns about European fishing quotas5, whilst on the eve of the election itself, the Party held a rally of 12,000 supporters at Alexandra Palace which they claimed was the largest political gathering of any Party since World War Two6.

On polling day in 1997, the scene was well and truly set for the British political applecart to be upended by James Goldsmith’s incredibly well financed single issue Party. His total spend, originally forecast to be around £20 million in just two years, ended up exceeding £35 million in total. By contrast, Labour spent an estimated £7m and the Tories £13m on their 1997 campaigns. Goldsmith’s Party had not only outspent them, but had turned up with new and dynamic anti-establishment messages, innovative and sensationalist marketing tactics, and a penchant for stretching the truth.

The Failure

The Referendum Party picked up 811,827 votes, approximately 2.5% of the total, and won zero seats. It lost 505 of it’s 547 constituency deposits by falling to reach a 5% share of the vote. In Reigate, their only MP George Gardiner came fourth behind the three major parties, before quietly switching his allegiance back to the Conservatives a few months later. Goldsmith stood himself in Putney against David Mellor, who had become a poster boy for Tory sleaze. He won only 3.5% of the vote and Labour won the seat. So disappointing was this result, that the defeated Mellor used his concession speech at the count to attack Goldsmith and label his Party a failure, only to be met with ferocious chants from Goldsmith and his supporters of ‘Out! Out! Out!’, providing one of the most dramatic incidents of the night.

The huge landslide victory for Labour meant that even if the Referendum Party had picked up a few MPs, they would have been easily ignored by the new Blair government anyway. The plan had been to win a few MPs which could then hold significant influence over a small or minority Tory government; a situation that in many ways finally happened in the aftermath of the 2017 election, as the ERG dragged Theresa May to where they wanted her to be on multiple issues.

On a simple ‘pounds spent’ versus ‘votes cast’ metric, the entire endeavour had been a huge failure. Exactly what Goldsmith might have done next though, we will never know. He died just a few weeks later in July 1997, aged only 64. He had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and warned that contesting the election could shorten his life. For whatever reason, the Referendum Party had become so important to him that carrying on with full throttled vigour was his response. Upon his death, the Referendum Party essentially ceased to exist. Another anti-European party founded in 1993 picked over its bones, with it’s charismatic Party Chairman putting in a lot of effort into not only sweeping up members and candidates, but also co-opting much of it’s political language and public positioning. That party was UKIP, and its Party Chairman was Nigel Farage7.

The Referendum Party is perhaps one of the finest examples of how utter, dismal failure can still be the genesis of future success. James Goldsmith’s personality-first approach to Euroscepticism failed in 1997, but it created a blueprint for Nigel Farage to copy. A few adjustments were made of course; the classic ‘Nigel Farage drinking a pints whilst having a cigarette’ photo opp was all about creating a more ‘man of the people’ persona, compared to Goldsmith’s ‘I know what’s really happening’ grandstanding. But the Referendum Party’s expertimental tactics, fiery, adversarial language and memorable, carefully crafted patriotic soundbites created a new anti-European lexicon that permeated not only all future polical debate on the issue but also various right-wing media outlets. Most people only leave a legacy as big as that in British politics after decades of public service. James Goldsmith and the Referendum Party, despite now being almost entirely forgotten, did it in 36 months.

Thank you for reading.

Further Reading

If you want to learn more about James Goldsmith and how he and a few other financiers transformed British business in the 1960s and 1970s, then watch ‘The Mayfair Set’, a four-hour, four-part Adam Curtis documentary on iPlayer.

‘Blair’s Babes’ was the rather jarring label created by the media to describe the official end to Parliament being dominated by men. The 1997 election saw 120 women elected as MPs (101 of which were for Labour), which was double the 60 women elected in 1992. It was a seminal shift in British politics that has happily stuck (in the 2019 election, 219 women were elected as MPs) and the blasé and dismissive commentary from contemporary mainstream media at the time is another healthy reminder that the 1990s had a serious sexism problem.

Echoes of this remain today; most people still know that Walkers have strong ties to Leicester, that Cadbury are from Birmingham and built the village of Bourneville, that Rowntree were from York, Coleman’s from Norwich, and so on. Such regional brands and businesses were Goldsmith’s favoured prey, which he then incorporated into Cavenham Foods.

The new breed of cut-throat modern financiers, of which Goldsmith was a de-facto founding father, loved going after family owned businesses, as they viewed the family owners as inevitably clueless and out of touch with modern capitalism. Many such companies were the largest employer in their local area, commonly employing multiple generations of the same family. As a result, most did not have a relentless capitalist focus on margins, shareholder value or profits out of choice, rather than incompetence. Instead they were often much more interested in things like their reputation in the local community, improving staff welfare and living conditions, and the founding family’s own standing in wider society.

A currency pegging (i.e. fixed exchange rate) system that tied the value of the Pound to the Deutschmark. It was the first major step on the road towards European currency union and the UK’s sudden exit not only lost the Bank of England billions but also sent interest rates soaring to 15%, triggering a recession and housing market flash-crash.

A euro-sceptic PR play lifted by Boris Johnson during the 2019 General Election where he turned up at a Grimsby fish market extolling the virtues of his ‘oven ready Brexit deal’ for the fishing industry, three days before polls opened.

That claim frankly, doesn’t make much sense when you start to think about it, in much the same way that sending asylum seekers to Rwanda for ‘processing’ also doesn’t make much sense once you start to think about it. A Priti interesting coincidence.

Another direct political legacy exists through Goldsmith’s son Zach, who was elected as a Conservative MP for the seat of Richmond, London in 2010 and in 2016 he ran for London Mayor, finishing second to Labour’s Sadiq Khan. He has consistently been an enthusiastic Brexiteer, resulting in him losing his seat twice to pro-Remain Liberal Democrat candidates in 2016 and 2019. Boris Johnson appointed him to the House of Lords in early 2020.