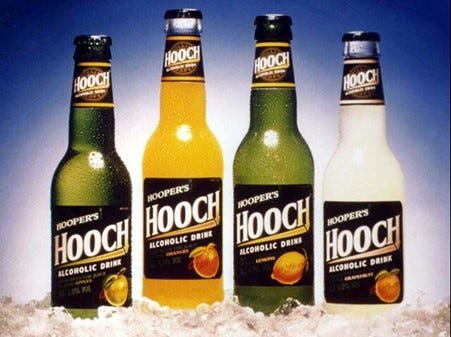

Hooper's Hooch (1995)

The story of the rise of the 'alcopop' and how one brand changed the British drinks industry forever.

In 1995, a brand-new drink was launched by Bass, one of the UK’s oldest breweries. Just two years later, that same drink had almost single-handedly changed the UK alcohol industry forever. Five years later, bruised, battered and defeated from the affair, Bass was chopped up and sold to the highest bidder, bringing down the curtain on over 200 years of success. This is the story of Hooper’s Hooch.

Bass Brewery and the Beer Orders

Bass were founded in Burton-upon-Trent, Staffordshire in 1777. One hundred years later, Bass was famous across the British Empire and was officially the largest brewery in the world, with an annual output of one million barrels. Much of its success was built on its early pioneering attitude towards building familiar brands; an approach that led to Bass petitioning Benjamin Disraeli’s government for new legislation to protect brands from imitation and fraud. On January 1st 1876, the Bass ‘red triangle’ logo became ‘UK Trade Mark 001’.

A century later Bass was still an iconic brand and was firmly established as one of the ‘Big Six’ who dominated the British brewing industry (the others being Allied, Courage, Grand Metropolitan, Scottish & Newcastle and Whitbread). All six not only sold incredibly popular brands of beer but also were ‘vertically integrated’ businesses, that owned thousands of ‘tied pubs’ who automatically stocked their products. The only real change to this very stable post-war status quo was the popularity of lager. In 1967, lager was just 4% of the UK beer market; twenty years later in 1987, it was 45%. Bass, with it’s long established expertise in beer brewing, adapted to this consumer change well and owned two of the most popular lager brand in the UK; Carling Black Label and Tennent’s.

In 1989, Margaret Thatcher’s government did to the beer industry what it had done to countless others, when it passed legislation to expose it to the powerful forces of competitive global capitalism. At the time, 75% of the UK’s beer market was controlled by the Big Six and the industry was accused by government of operating a ‘complex monopoly situation’. In particular, they called out that pub landlords had almost zero freedom in terms of what brands they stocked, and also had to pay fixed rate-card prices decided by the brewer, rather than the price set by an open or competitive market1. This guaranteed the brewer both very healthy margins and consistent sale volumes, disincentivising investment and innovation. Meanwhile, consumers were faced with severely restricted choice, regular price rises and a general sense of stagnation and decay across the UK’s entire estate of pubs.

The Beer Orders came into effect in December 1989 and restricted the number of ‘tied pubs’ that any one brewery could own to 2,000. It also forced all of the Big Six to stock at least one ‘guest beer’ from a rival brewery and to publicly publish their rate cards to drive more price competition. Bass, the oldest of the Big Six were rocked to their core by the changes, as they owned approximately 7,000 pubs across the UK. They and other members of the Big Six were given three years to dispose of their ‘excess’ estate.

Many responded by creating ‘pub owning companies’ or ‘pubcos’ to enable them to manage their excess pubs at ‘arm’s length’, with much less restrictive stock and pricing controls than a tradtional tied pub. Whitbread meanwhile decided to start exiting the industry entirely, selling over 2,500 pubs within two years and refocusing on casual dining and hotels. In 1995, they used the money from these sales to buy Costa Coffee for £19million; investing heavily to turn what was just a small chain of 39 coffee shops at the time, into the biggest coffee shop brand in the UK today2.

The ‘Ready to Drink’ Revolution

Around the same time that the Big Six were being lambasted for ‘cosy competition’ and a lack of innovation, a relatively small, family-owned spirit business started a revolution. After two years of careful research and product development, the Beefeater Gin Company launched a strange stubby glass bottle with a ring pull. It was the UK’s first ever ‘ready to drink’ (RTD) spirit and mixer product.

Originally designed as a ‘summer season only’ novelty product that would capitalise on the growing popularity of gin and tonic, sales dramatically exceeded initial expectations. Production was rapidly expanded and the following year Beefeater launched two whisky versions (with lemonade or ginger ale). The handy little bottles could be taken to the park, the beach or the cinema and could even fit into most jeans pockets. Popularity boomed, driven by both convenience and the intangible but powerful force of ‘being cool’. By 1986, Beefeater had rolled out vodka and rum versions too, and the heads of the biggest brewers in the UK had been well and truly turned.

Beefeater had grabbed the ‘first mover’ advantage and created a brand new market but The Big Six and others were getting ready to spring into action. In 1987, family-owned Beefeater was bought by Whitbread, almost entirely due to its recent success in the RTD sector. The rest quickly identified an alternative opportunity. Beefeater were known almost entirely for their very famous gin brand and did not have recognisable brand names in other spirits. Instead, unidentified and generic spirits were used in their vodka, whiskey and rum RTDs, meaning anyone owning a powerful and famous spirit brand could gain a huge competitive advantage if they could put them into the same ‘ready to drink’ format.

In the early 1990s, Bass executives were actively looking for new innovations to replace the significant loss of ongoing revenue and financial security caused by the Beer Orders. Unfortunately, the new ready to drink market was a busted flush, as they didn’t own a popular, famous spirit brand. They watched enviously as United Distillers launched their Gordon’s RTD range in 1991, followed by Malibu in 1992. Then in 1993, the granddaddy of them all entered the fray when Bacardi launched the Bacardi Breezer. As one of the largest privately owned businesses in the world (then, and still today), this marked that the ‘ready to drink’ market was no longer a new, experimental frontier but a hugely profitable growth opportunity.

Two Dogs and Hooch

In 1994, still locked out of the RTD market by their lack of spirit brand name, Bass launched Caffrey’s Irish Ale (ostensibly a Guinness rip-off with a lighter brown colour). Whilst year one sales were okay, brewery management remained envious of opportunities elsewhere that were passing them by. Their savour came from Down Under.

Duncan MacGillivray was a respected Adelaide-based beer brewer and publican in his mid-40s, who had years before won the Australian Beer Award two years in a row. In 1993, he had a conversation with a farming neighbour, who was struggling with significant numbers of ‘excess and misshapen’ lemons that he couldn’t sell to supermarkets. He decided to brew them.

"I didn't like to see good lemons wasted, and I remembered a recipe I'd once heard from a friend's mother. I took some lemons back to my pub, tested various yeasts, and went through great trials and some pretty horrible errors before Two Dogs saw the light of day".

MacGillivray turned 40 crates of lemons into an ‘alcoholic lemonade’ with an alcohol content of 4.2% and stocked it in his pub, the Bull and Bear Ale House in downtown Adelaide. He called it ‘Two Dogs’ after a famous blue joke3. It was, to even MacGillivray’s surprise, the first brewed lemon alcohol drink anywhere in the world. It was also an immediate hit and within months, after being inundated with orders, he outsourced production to the established South Australian brewer Coopers. By the start of 1995, over 800 tonnes of lemons were being turned into 80,000 cases of Two Dogs every single month.

In March 1995, MacGillivray announced that Two Dogs would be launching into UK (the brand’s first foray beyond Australia) by the start of the summer, backed with a £500,000 media campaign. Executives at Bass, who had been watching these events with great interest, suddenly sprang into action. Two Dogs was a ‘ready to drink’ product made with no established spirit brand in it. Despite this, sales were exploding off the chart. If they were coming to the UK, then Bass would take them on.

From a standing start, Bass went from the decision to make their own ‘hard lemonade’ to having their own branded product rolling off the production line in seven weeks. This quite remarkable feat revealed just how much pent-up desire and energy there had been within Bass to go ‘all in’ on a new opportunity. Named after the 19th Century British chemist William Hooper to reflect it’s ‘home brew’ vibe, Hooper’s Hooch was the company’s new great white hope. Unbelievably, taking advantage of the six-week journey that the 40,000 cases of Two Dogs had to make by sea, Bass ended up beating Two Dogs to launch by two weeks, making Hooper’s Hooch the first ‘hard lemonade’ to officially launch in the UK by a hair.

Hooper’s Hooch was an instant hit with consumers, who found that it tasted good and made them feel good in equal measure. Annoyed by Hooch beating them to the punch, MacGillivray flew out to the UK within weeks and licensed three UK based breweries to start brewing Two Dogs. By August 1995, thousands and thousands of cases of both Hooper’s Hooch and Two Dogs were being produced and sold every week in the UK.

Alcopop Mania

The summer of 1996 was the summer of Football’s Coming Home, TFI Friday and Oasis playing Knebworth. The mood was one of revery and much it was fuelled by a new, trendy drink – the alcopop, which had now enteted the national vernacular. Numerous alternatives and competitors were being launched almost weekly in the wake of the runaway success of Hooch and Two Dogs, the most notable being WKD, which arrived that spring4.

That summer, British drinkers were getting through an astonishing 2.5 million bottles of Hooch every week. It was estimated to hold over 70% of a market already worth £250 million a year. Bass executives were ecstatic. But significant problems were already visible. The first prickles of discontent emerged in the run-up to the Christmas of 1995, when parent groups raised the concern that alcoholic drinks labelled as ‘lemonade’ would encourage under-age drinking. In early 1996, Bass executives received a letter from the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) demanding they withdraw an advert, which they deemed was overtly appealing to under-age drinkers5.

Despite being in hot water, Bass executives were initially non-plussed. They saw the negativity as part of a broader backlash to 90s youth culture and the edgy, experimental ‘Cool Britannia’ energy seizing the country. This was certainly happening; a Club 18-30 outdoor advertisement featuring the copy ‘Beaver Espana’ was banned around the same time. Despite the controversy, bookings with the holiday group surged. A Calvin Klein advert, featuring Kate Moss lying down naked on a sofa, was also met with public outcry. Sales of CK underwear soared. Bass pulled the advert as required, but at the same time made the decision to increase the alcohol strength of Hooch from 4.2% ALC (the same as Two Dogs) to 4.7%; a move they expected would help fuel even more demand from their target audience of energetic 20-something drinkers who ‘drank to get drunk’ and have fun.

The Portman Group

Back in 1989 and under threat from government regulation, the biggest names in the UK alcohol sector (including Bass) got together to launch a new organisation. The Portman Group was named after Portman Square in London, where it was first concieved at a meeting in the Guinness head offices. It was founded as a research-sharing centre to enable impartial and accurate data to be collected around UK drinking habits, behaviours and brand preferences, with the costs shared by all major alcohol manufacturers.

In early 1996, increasingly worried about growing criticisms of the effects of the ‘alcopop boom’ and alarming headlines about a surge in under-age drinking, the Portman Group announced it would be creating and publishing a new ‘Code of Practice’. This would help ensure the industry stayed within specified boundaries when it came to branding and advertising.

In April 1996, the pressure group Alcohol Concern published a report entitled ‘Pop Fiction: The Truth About Alcopops’, creating a tsunami of negative media coverage about the impact of the drinks, particularly on young people. Just a few weeks later, the Portman Group Code of Practice was published. It was aggressive in its approach, outlining clear new guardrails to significant curb the encouragement of under-age drinking, excessive alcohol consumption and anti-social behaviour. The code also took aim at retailers; whilst it was illegal to sell alcohol to under 18s in the UK, many retailers had inconsistent or even non-existent enforcement policies.

The fallout from the Portman Group’s new code was swift and immediate. Carlsberg withdrew their new product ‘Thickhead’ just two days after it’s launch. Most supermarkets underwent significant in-store changes to ensure alcopops were stocked and displayed as an age-restricted product. Other stores announced new and improved training schemes for staff.

Hooper’s Hooch, as the biggest brand in the ‘alcopop’ sector had already started to become the infamous ‘poster boy’ and lightning rod for media and political criticism. Many brand managers would instinctively look to keep a low profile, but this approach was thoroughly rejected by Bass, who were desperate to keep the significant profits generated by their market leadership position. Just weeks after the Code was launched, the first ever Hooch TV advert aired on prime-time Channel Four.

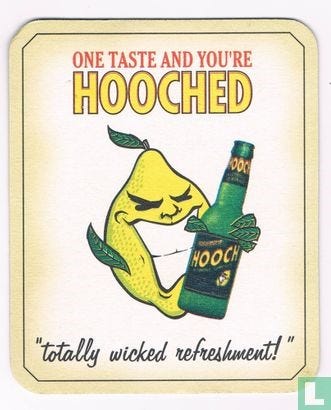

In September 1996, in its first set of rulings on the alcopop industry, the Portman Group ruled that Hooper’s Hooch was in breach of the Code. The ruling stated that the ‘cartoon lemon character’ that featured on every single bottle of Hooch was ‘appealing to under 18s’ and ‘must be removed entirely’ from all future product marketing. Ian Morris, Director of Communications at Bass responded that they “were disappointed [with] the opinion… our market research shows that our fruit character has not appealed unduly to under 18s”. However, they had no choice but to comply, given Bass was a founding member of the Portman Group.

All Hooch TV adverts (some of which had been shot but had not yet aired) were re-edited to remove all visible references to the ‘cartoon lemon’ bottle. A new brand tagline was also established and inserted into the existing creatives; ‘refreshment that deserves respect’. The total cost of the product write-off and re-design was over £1million.

The Wheels Come Off

With some of the most inappropriate and wild marketing being stamped out by the new Portman Code, attention quickly turned to the other side of the problem with alcopops; categorisation. Truthfully, the biggest reason that the alcopop sales had taken off like a rocket was that they had quite deliberately slipped through gaps in regulation. This sleight of hand goes right back to the genesis of Two Dogs, as MacGillivray explains.

"At the time most of the pubs in Australia were tied to breweries which largely dictated what beer they could stock. Publicans worked out very quickly that Two Dogs wasn't beer so they could put it on tap without contravening the restrictions of their agreements”

Two Dogs went from leftover lemons to sales phenomenon in three months because of a quirk of the system. In the UK, Bass and Two Dogs worked together to ensure the quirkyness of the ‘new’ alcopop category delivered similar advantages, lobbying for both products to be classified by the government as a ‘low strength wine’ (or ‘wine cooler’). This meant that the tax and duty was low; much lower on a 4.7% ALC alcopop than a similar strength beer. This meant that in the UK, alcopops really were the cheapest way to get drunk, whilst still providing ample opportunity for a healthy profit margin for the producer. This was the real reason Bass executives were so excited about booming Hooch sales 1995; it was putting huge amounts of cash straight onto their bottom line, and proving that their struggling brewing business was still a success.

As a direct consequence of the work of Alcohol Concern and The Portman Group, in November 1996 the Conservative Chancellor of the Exchequer Ken Clarke equalised the duty rate between beer and alcopops. The net effect was a 10-15% increase in the cost per bottle or can. This was a nasty blow for the sector, but confidence in the long-term profitability of the new, growing market remained high. This was reinforced weeks later when Pernod Ricard shocked many in the industry by announcing the purchase of Two Dogs, buying out Duncan MacGillivray’s 70% equity stake entirely.

At the start of 1997, Bass executives expected a calmer year ahead. Marketing budgets were increased to help Hooch protect it’s #1 position in the sector and to keep sales growing despite the inevitable price increases from the duty and tax reform. Unfortunately, the UK government wasn’t done with them yet.

In May 1997, Ken Clarke was replaced at the Treasury by Gordon Brown, as The Labour Party ended eighteen years in the wilderness with a landside victory under Tony Blair. On 16th May, just two weeks after taking office, the new Home Secretary Jack Straw ordered an urgent review into the sale of alcopops. The trigger for this review was shocking new research that revealed over half of Britain’s teenagers were regularly drinking alcopops, including children as young as 11 years old.

Up to this point, the alcopop industry had been chastised, criticised and given several ‘tellings off’. This time the response was louder and angrier, fuelled by the first real academic data on the impact of the new drinks and the feeling that not enough had been done by the manufacturers to address previous criticisms. The day after the Home Secretary’s announcement, The Daily Express ran a front page with the headline ‘Time to Ban Alcopops’. Alcopops and in particular, industry leader Hooper’s Hooch, were now bogeymen ruining the lives of British children by prioritising profits over societal wellbeing and national health. For a nation that had just changed governments for the first time in a generation, the outcry was loud and clear; we won’t stand for this any longer.

The Portman Group immediately issued an update to its Code, making it even tighter and more restrictive. The Co-Op Group, so often the first to take action in response to changing UK attitudes, announced in June 1997 it would no longer sell alcopops in any of its 1,200 stores. Days later, Iceland announced it would follow suit. Then, JD Wetherspoons, a nationwide pub chain, put out a press release stating all pubs in their network would cease stocking alcopop products immediately. The tide had well and truly turned.

Many manufacturers who had only launched alcopops due to bandwagoning, were now seeing huge potential reputational damage for increasingly minimal rewards. Many simply cut their losses and discontinued their products, sending brands like ‘Lemonhead’, ‘Vault’, ‘Barkers Liquid Gold’ and ‘Zanzibi Sling’ to an early grave. At the first ever ‘National Conference for Alcopops’ at Leicester University, no alcopop producers turned up, afraid of being met with media or public hostility. Hooch meanwhile was not only the market leader for the category, but the very public removal of its ‘cartoon lemon’ from its branding just 6 months earlier (which it had both moaned about and only tweaked slightly rather than redesigned) had already established itself as a bad actor. The brand and Bass were forced to asborb the brunt of the outrage.

Aware that they had ended up on the wrong side a dividing line, Bass announced they would reduce the sugar content of Hooch to make it less palatable for teenagers. They also announced another rebranding, this time a proper redesign to an ‘unambiguously adult look’. However, they refused to change the ALC content, knowing that reducing it from 4.7% would inevitably hit sales.

It’s All Downhill From Here

Despite the changes the damage to the brand was significant and by the start of 1998, sales of Hooch had fallen 30%. Bass responded by heavily investing in marketing, pumping over £8million into advertising. However, by mid-1998, they were no longer the market leader, with Barcardi Breezer becoming the #1 brand in the ‘flavoured alcohol’ category.

Bacardi had spent the previous five years staying firmly on the right side of the rules and growing slowly but steadily through targeting an older adult audience (particuarly 25-45 year old women) and was positioned at a more premium price point. That success triggered competitors to launch two new vodka-based products, Smirnoff Ice and Red Square, which also positioned themselves as premium, lifestyle drinks for more middle class types.

Executives at Bass fought hard. Trying to get into the same market as Bacardi, in 1999 they introduced a ‘low calorie’ version of Hooch aimed at professional women. In 2000, with Red Square and Smirnoff Ice making waves, Hooch added the word ‘vodka’ to the product label and changed the glass bottle from green to clear. But the entire process was one of managed decline.

Outflanked by the big-guns Bacardi and Smirnoff in the older, young professional market, the game was up when Hooch lost it’s grip on the 18-24 market too. The culprit was WKD and it’s impactful new ‘Do you have a WKD side?’ adverts that made it the new, edgy and ‘cool’ drink of choice. Battered, bruised and tired, Hooch could do little more than watch as it’s once distinct market positioning and stable ‘repeat purchaser’ sales base was stolen by a competitor.

Aftermath and Epilogue

Hooper’s Hooch was Bass Brewery’s last big bet. It looked at one point that it’s future as the biggest brand in an exciting and growing new sector was all but guarenteed, but fatal damage was done between the summers of 1996 and 1997, dooming it to a slow death from competitors between 1998 and 2000. The fast, loose and somewhat reckless attitude that encapsulated Hooch was reflective of the culture of the time, but it was also driven by how Bass were a struggling business looking to capitalise on something new it did not quite understand.

In June 2000, Bass announced that the entirety of its brewing operations, including Hooch, were to be sold for just over £2billion to a company that did understand how things worked in the modern world; Belgium’s Interbrew, makers of Stella Artois. One year later, the remaining non-brewing business of pubs and hotels including All Bar One and O’Neills, was renamed ‘Six Continents’, signalling the end of the use of the ‘Bass name’6. In 2003, after two years with almost zero marketing investment, Hooper’s Hooch was officially discontinued by it’s new owners.

In 2012, after nearly a decade away, Hooper’s Hooch was surprisngly raised from the dead. The owners of the brand were now Molson Coors, who leased the rights to Global Brands, best known for ‘VK’ and Corky’s shots. The Hooper’s prefix was scrapped, the ALC content was reduced from 4.7% to 4.0% and an advertising campaign featuring Keith Lemon (geddit!?) re-launched the brand into the modern era. This version of the drink is still produced today and is avaliable in most large UK supermarkets and off licenses.

In 2016, in an almost unbelivable incident, the Hooch was in trouble again, as one of it’s adverts was banned by the ASA for appealing to under-age drinkers. I guess you can’t teach an old drink, new tricks.

Thank you for reading.

Not only did breweries ‘ban’ rival beers, but they often ‘pushed’ their own mixers, soft drinks and even snacks into their pub estates at the expense of much more widely known and desirable brands like Schweppes or Walkers. Today, the only UK wide pub chain still operating this 100% tied model is Sam Smiths. Their crisps are rubbish.

As of 2022, Costa Coffee have approximately 2,700 stores in the UK, putting in miles ahead of its competitors including Starbucks (c. 750) and Café Nero (c. 650). Other brands in Whitbread’s modern business model include Premier Inn, Beefeater and Brewers Fayre.

From modern perspectives the joke is dated and distateful, due to being based on Native American stereotypes. The joke was popular at the time due the success and impact of the 1992 film ‘Last of the Mohicans’. The joke is:

A little Native American boy asks the chief of his village: “Why is mummy called Little Running Stream?” The chief replied: “Well, when your mummy was born, I looked out of the teepee, and the first thing I clapped eyes on was a little running stream, and that was what I called her.”

The boy then asked: “So why is daddy called Big White Cloud?” The chief answered: “When your daddy was born, I looked out of the teepee and saw a big white cloud, so that was what I called him. Why do you ask, Two Dogs Fucking?”

Each bottle and can of Two Dogs featured the slogan ‘Why do you ask?’ written on the label, as a nod to the origin of the brand name.

Another ‘new’ alcopop brand launched during this time was a ‘Caribbean’ flavoured alcopop called Tilt. It’s creators were immediately taken to court by lawyers representing Coca-Cola, who felt the product was a direct infringement on their Lilt brand. Tilt became the first alcopop to be forcibly withdrawn from the UK market, for copyright infringement.

The ASA had a torrid 1996, caught in the middle of an inflection point of culture, and brands and advertising executives starting to be bolder, braver and more experimental. This creates a lot of debate, leading to the ASA being accused of being totally ineffective by some campaigners, whilst others criticised them for ‘playing God’. This dynamic culminated with the ASA stuck in the middle of a huge political argument about an advert for the Conservative Party, called ‘Demon Eyes’.

The pub brands within Six Contintents were soon disposed of and the remnants of the ‘Six Contintents’ group spun out of Bass is now known as ‘InterContinental Hotel Group (IHG) and owns brands including Holiday Inn and Crowne Plaza.