Bruce Forsyth's Big Night (1978)

The forgotten story of how Bruce Forsyth was the first victim of Britain's Winter of Discontent.

The Winter of Discontent began in November 1978 and ran into February 1979. It’s a pivotal touchstone in British political and cultural history and a phrase the media love to redeploy in headlines even nearly 50 years later. It’s a seminal moment; a threshold the UK collectively crossed, that blessed or cursed us with (depending on your political persuasion) the election of Margaret Thatcher and a decade of radical, permanent political change, the end of society, the rise of the yuppie and so much more. What most people don’t remember about The Winter of Discontent is that its first victim was Bruce Forsyth.

Brucie’s Early Years

In many people’s minds Bruce Forsyth is probably lumped into the broad category of ‘TV presenter’ but in many ways, that is a little bit like describing The Queen as ‘the woman we put on stamps’. Bruce Forsyth was ‘an entertainer’ in every sense of the word, making his TV debut at just 11 years old in 1939, on a TV show with an eerie foreshadowing title of ‘Come and Be Televised’. (The show’s almost naive sounding title also reveals just how new the medium was at the time).

By age 14, Brucie was singing, dancing and playing the accordion at theatres all over the UK, whilst being billed as ‘Boy Bruce, The Mighty Atom’. After the war and a stint of national service, Bruce not content with being a singer, dancer and musician also tried his hand as a comedian, and even a ‘strong man’ act, which was the genesis of his iconic ‘strong man pose’. These talents saw him spend the best part of a decade playing in church halls and theatres all over the UK, often sleeping in train luggage racks after a performance.

Around this time, one of his semi-regular gigs was at The Windmill in Soho1. The club would run five shows a day, each featuring three acts. The first act would be an entertainer (usually a magician or musician). The second act would be a comedian. The third act would then involve a troupe of young women performing a suggestive and salaciousness dance, such as the ‘Can-Can’. In the 1950s the UK was still a deeply repressed and quasi-Victorian society2 and the presence of all three acts meant the performance could be classified as ‘Variety Entertainment’, making it a resepectable middle class affair. In reality, the audience consisted entirely of young working men wanting to see some tits3.

The comedian, performing second and immediately before the show everyone really wanted to see, would generally be given extremely short thrift for his (legally required) 15-minute set. This environment is where Bruce Forsyth honed his craft4. Telling jokes to hundreds of drunk men (all of whom want you to get off the stage as quicky as possible) is probably the best training for handling the pressures of presenting live television there’s ever been.

Some of Bruce’s natural ability to entertain anyone and to make people feel at ease can be glimpsed in an anecdote from his Windmill years. In the summer, female performers would often take to the roof in between shows to catch some sun, bathing topless to ensure they didn’t get tan lines, but placing large 2 pence pieces on their chest to preserve their modesty from staff and other performers. Bruce used to enjoy popping up to the roof to wave hello to the girls, before pulling a one pound note out of his jacket pocket and loudly asking ‘has anyone got any spare change?’

Sunday Night at the Palladium

The year 1958 saw the launch of the world’s first transatlantic airline, the introduction of parking meters and work started on the building of the M1, the UK’s first ever motorway. The year also marked the arrival of Bruce Forsyth as a popular UK presenter and in many ways, he became just as familiar as long-haul flights, high-speed driving and parking tickets did over the course of the rest of the century.

His TV breakthrough came when an ITV producer attended a show featuring Brucie and comedian Dickie Henderson. Blown away by both of them, ‘The Dickie Henderson Half Hour’ was commissioned as a vehicle for the latter, whilst Brucie was entrusted to take over from Tommy Trinder5 as host of ITV’s ‘Sunday Night at the Palladium’, which was already one of the biggest shows on TV, most famous for its segment ‘Beat The Clock’, one of the very first TV gameshow moments.

Broadcasting live from The London Palladium, the show beamed popular UK variety acts directly into the homes of those lucky enough to own a TV. The timing of Bruce’s big break was perfect, cleanly catching the wave of TV ownership explosion and making him one of the first TV presenters to have access to something approaching a nationwide audience6. Furthermore, British TV was finally hitting its stride in terms of content output too. In 1957, the BBC and ITV finally started to broadcast more than ‘just’ 12 hours per day, whilst the government also agreed to scrap the ‘Toddler’s Truce’; a legal restriction that meant both TV channels had to go dark between 6pm and 7pm every single evening to allow parents to put their children to bed.

Perhaps then, being given a presenting job on a huge show in 1958 was a huge stroke of luck, but in true Brucie style, he seized the opportunity fully. His presenting style perhaps best described as ‘warm and chipper’ made the audience at home feel just as welcome as the audience in The Palladium itself and revealed an unbeknownst truth about Bruce Forsyth; he was a ‘TV natural’ before anyone had even worked out what a ‘TV natural’ was.

With an effervescent host and regular Sunday evening slot, ‘Sunday Night at the Palladium’ become one of the first ‘appointment to view’ shows in British TV history. By January 1960 an edition featuring Cliff Richard and The Shadows was watched by more than 20 million people, an ITV record. The show started to attract some of the biggest names in the world, including Judy Garland, Bob Hope, Liberace and the Rolling Stones. Things were very much on the up-and-up, with only one small hiccup enroute. In 1961, a strike was called by the British Acting Union ‘Equity’, meaning all performers were pulled from the show. Bruce and his friend Norman Wisdom performed the entire show themselves, endearing Bruce to the nation even more for his ‘the show must go on’ gusto.

Brucie’s Sunday night behemoth reached its cultural zenith when The Beatles' publicist Tony Barrow claimed that the band's first appearance on the show in mid-October 1963 was the spark that created Beatlemania in the UK. The high-water mark in hard numbers came a few months later in April 1964, in a show featuring The Bachelors, Hope and Keen and Frank Ifield, which reached 9.4 million households, and an estimated 30 million people.

The only problem for Brucie was the relentless nature of the show; requiring live broadcasts almost every single Sunday night, preventing him from joining touring productions, doing lucrative full summer season residencies, or joining a West End cast. This led to him taking a short break in 1960 so he could do some national touring, but by late 1964, Brucie realised he needed to depart the show that had made him a national icon in order to chase new ambitions7.

The West End, Hollywood & The Generation Game

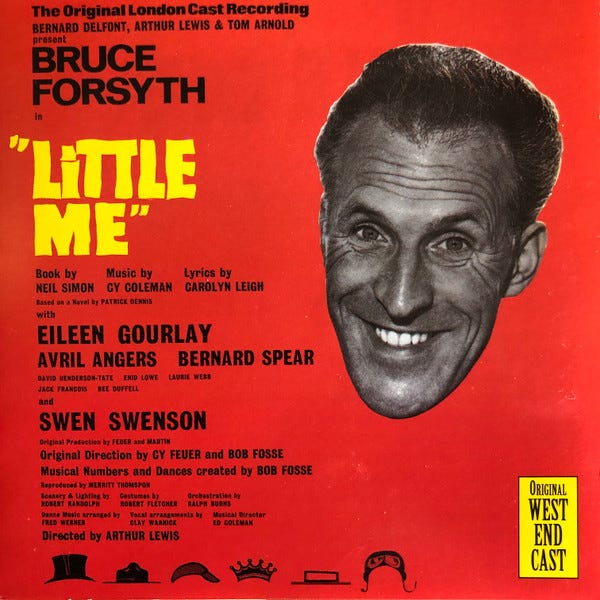

From late 1964, Bruce took up a leading role in the West End debut of multi-Tony award nominated musical Little Me, with him being the ‘face’ of all the show’s marketing.

Whilst the show ran for a highly credible 334 performances at the Cambridge Theatre (one of London’s largest venues), reviews were notably lukewarm, particularly for Brucie’s performance, which may have been a little too ‘hammy’ for London’s very posh theatre critics. This however, didn’t stop him crafting out another huge opportunity for himself by being cast in the 1968 film Star! which was directed by Robert Wise and starred Julie Andrews. The same duo had collaborated in the mega, mega, mega hit The Sound of Music in 1965, whilst Andrews was also coming off the back of Mary Poppins in 1964. Star! was going to be the biggest hit of the year and Brucie was going to be part of it.

Of course, Star! Was a huge flop. Critics reviewed it relatively favourably, but audiences expected something akin to Sound of Music Part 2 and once they realised that this was not at all what the film was, they stopped going to see it. The film made an estimated $15 million loss and Brucie’s Hollywood career, carefully planned to be built on the foundations of a ‘sure thing’ as a first film, was over before it even begun8. In the end a different musical film with an exclamation mark at the end of it’s one word name turned out to be the mega-hit of 1968; Oliver!.

Unfortunately, this flop was not even the lowest moment of 1968 for Brucie, as that year he also released a single called ‘I’m Backing Britain’, as a tie-in to a government endorsed initiative to support British businesses announced in the wake of the national embarrassment of a Sterling devaluation in late 1967. The chorus of the uplifting tune claimed, ‘The feeling is growing, so let's keep it going, the good times are blowing our way’. The song failed to chart.

Perhaps unsurprisingly then, in 1971 Brucie went back to what he did best and became the presenter of a new BBC show designed to make the King of Sunday evening in the 60s, the King of Saturday night in the 70s. The show was called ‘The Generation Game’ and it took Forsyth’s career to new heights. The format was built around him, incorporating ‘Beat The Clock’ from his Sunday Night days as well as numerous other games. Every episode opened with Bruce striking his ‘strongman pose’ in silhouette, and it was the birthplace of ‘Nice to see you to see you’, ‘Good game, good game’ and ‘Didn’t he/she do well?’. Brucie even wrote and sang the theme tune ‘Life is the Name of the Game’. With the show completely built around him, Bruce was once again one of the most famous entertainers in the country, as The Generation Game quickly became one of biggest shows on UK television, regularly exceeding 20 million viewers.

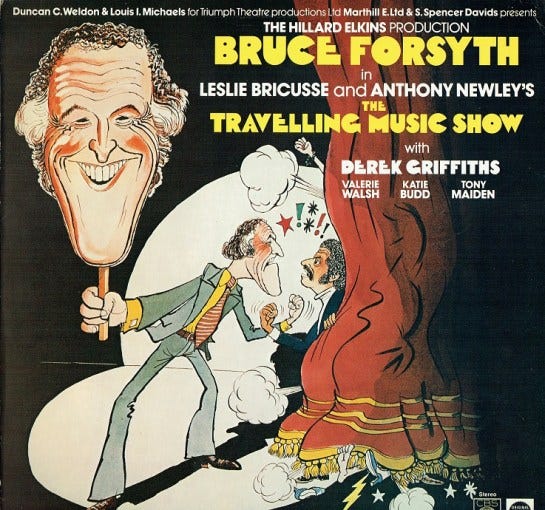

After seven hugely successful series, something quite unexpected happened. Bruce quit. According to the man himself, he was worried that the incredible success of the show was not going to last forever and that he needed to get off at the top of the elevator. He stepped off and launched The Travelling Music Show, a stage ‘jukebox’ musical loosely based on his own life and career.

Sometimes in the arts, the dividing line between a passion project and a vanity project can get awfully blurry and it’s a little unclear which side The Travelling Music Show belongs to. In the show, Bruce played the role of ‘Fred Limelight’, a name which wins points for ‘Passion Project’ because it’s a fictional name rather than him playing a version himself, but then also wins points for ‘Vanity Project’ because the surname of the character is literally ‘Limelight’. Brucie’s dream was a successful UK run and nationwide tour, followed by a transfer to Broadway but it reviewed badly and closed after just four months9. The only lasting impression the show left, was that Bruce grew a moustache for the role of ‘Fred Limelight’ and kept it for the next 40 years.

Bruce Forsyth's Big Night

Bruce might have failed with The Travelling Music Show but it was always a bit of a long shot; creating a big hit musical or theatre production is notoriously difficult. Almost as soon as it was clear it wasn’t working out, the BBC were back in touch with Bruce to bring him home to the Beeb. His judgement about The Generation Game reaching it’s zenith however was wrong. Under new host Larry Grayson, the show had somehow gotten even bigger, and would eventually eclipse 25 million viewers in 1979; a full 5 million more than Bruce was pulling back in 1976. He couldn’t go back but that was fine, because the BBC would find him a new show to present. Except they wouldn’t.

That’s because Michael Grade, Chief Controller of ITV, blew them out of the water. ITV wanted to rip the heart out of BBC One and earlier in 1978, they had done exactly that by poaching Morcambe & Wise. Shortly afterwards, he signed the deal to bring Bruce back to ITV and it sent an absolute shockwave through the BBC that plunged the channel into a state of crisis, resulting in a number of years of BBC One being second best to the financial firepower of their noisy neighbour on channel three. Eventually, the BBC found the perfect solution to this problem; Michael Grade became the Chief Controller of BBC One in 1984.

Back in 1978, and fully aware of how badly ITV wanted him, Bruce got himself a massive golden handcuffs deal (rumoured to be worth a whopping £15,000 per episode) and a 2 hour Saturday night prime-time slot with a huge £2million production budget to go with it (roughly £250,000 an episode, making it one of the most well funded shows on TV). The show itself would be a blank canvas vehicle for Bruce and his many talents.

And thus, Bruce Forsyth’s Big Night was born and it was immediately one of the most highly anticipated progammes on TV. The name wasn’t great, but it was no better or worse than Ant & Dec’s Saturday Night Takeaway. In terms of the contents of the show, the best way to understand it is to read this advertising copy, straight from the mouth of Brucie himself, that featured in The TV Times, announcing the show ahead of it’s launch in October 1978.

Saturday evening at 7.25, and the show I’ve called – modestly – Bruce Forsyth’s Big Night. We’re aiming to make it the fastest moving, most fun-filled package on television. You’re going to meet international stars, such as Sammy Davis Jr and Dolly Parton. Then I’m inviting Charlie Drake along every week to repeat his success in The Worker. We’re also recreating The Glums, and the days of wireless – radio, to you. And we’ve the comedy duo Cannon and Ball. What’s that? They’ll go with a bang? Let’s get it straight – I do the gags, you join in with the games, OK? We’ve a number of those, including Teletennis and The 1000 Pound Pyramid, and Anthea is going to help me with them. Also appearing will be the poetess Pam Ayres, and Rod Hull and Emu. And as it’s a family show, we’re inviting the kids to Beat the Goalie, and to play the main roles in Doctors and Nurses, with stars as patients. As you can see, you’re going to do well, every Saturday night…no, dear, it’s not Saturday Night Fever. No, I’m not John Travolta. It’s Bruce Forsyth’s Big Night. And it’s going to be nice to see you, to see you nice!”

You might be thinking ‘sounds pretty shit, but I guess eentertainment has changed a lot since 1978’. Unfortunately for Brucie, it sounded pretty shit in 1978 too, relying far too much on slighly dated ideas and formats. The best example of this being the ‘Doctors and Nurses’ segment mentioned above, which gives off strong Carry On! vibes, yet 1978 was actually the year the very last Carry On! film was released.

Another of the the show’s big flaws can also be found in the promotional copy. Saturday Night Fever was released in the UK in March 1978 and the show looked to capitalise on the ‘Disco Fever’ gripping the nation, which was a massive, massive mistake. The result was that the show’s DNA was loud, ostensibly un-British and somewhat dated even at the time. Just watch the opening minutes of the very first episode and you will immediately see what I mean.

(The above clip is actually the entire first show. Skip to 29:00 for perhaps one of the most bizarre elements, ‘Teletennis’ which is literally, two old people playing Pong. This is then followed by a near-ten minute segment where Bruce judges a fancy dress contest. Remember, this show had a huge budget and aired in super ‘prime-time’).

Even at the time, getting through the whole show in one sitting (and in 1978, that was the only option avaliable) requires a fair amount of stamina. For a so called ‘light’ entertainment show, this is a cardinal sin. The producers quickly realised the error and after just a few episodes, the show was streamlined to a 90 minute slot including adverts, but the damage was already done. The first episode was the most watched TV show of the week, but the second episode didn’t feature in the Top 20. The reviews were brutal too.

The show that had everything; the star, the biggest budget, the best time-slot, and A-list guests (Bette Midler, Elton John and Sammy Davis Jnr all appeared) was one of the biggest flops in TV history. It’s last episode went out in December 1978 and everyone involved, including Brucie, knew another series would never be commisioned. Just as the UK was about to enter a state of such distress that it would change the socioeconomic future of the nation forever, Bruce Forsyth, the most popular entertainer in Britain, was ruined.

Aftermath

Big Night was dead but Bruce’s golden handcuff deal meant he was going nowhere. For over a year he sat in TV limbo land before he got given a new show to front. This time it was not something built from the ground-up specifically for him, but a cheap, basic gameshow format bought from an American production company. It needed a host and Bruce needed a show. The show was called Play Your Cards Right and it’s first episode aired in February 1980. Brucie’s showmanship, cheeky patter, cheesy catchphrases and effortless presenting style made him the perfect host for a lighthearted game that revolved around little more than luck. It was an immediate smash hit.

Just as Brucie was back at the top, he also got to enjoy the schadenfreude of watching The Generation Game getting cancelled in 1982 after Larry Grayson quit. Brucie’s Play Your Cards Right went from strength to strength, resulting in an impressive 120 episode run that lasted all the way through to 1987. Then in 1990, Bruce made a spectacular, sudden return to the BBC, and after being off-air for eight years, The Generation Game was brought back from the dead for him and thrown back into it’s old Saturday night prime-time slot. The magic was still there and it was a ratings hit, running for 5 additional series.

Then in 1995, Bruce shocked TV land again with a switch back to ITV. After being off-air for eight years, ITV brought Play Your Card's Right back from the dead for him. The magic was still there and it was a ratings hit, running for 6 additional series until 1999.

As remarkable as all that is, especially after the low, low ebb of 1977-1978, it is even more remarkable considering this article hasn’t even yet touched on his final career twist. By 2004, with both The Generation Game and Play Your Card’s Right long since deemed as dated and permamently cancelled, his career was officially dead. A one-off gig presenting an episode of Have I Got News For You put him back on the radar of TV producer-land, culminating the following year with him being given a trial as the lead presenter on another new, live Saturday night prime time show called Strictly Come Dancing. He presented it for an incredible 11 consecutive series until ill health forced the octogenarian off air, shortly before his death in 2017. Today, Strictly remains the jewel in the BBC’s light entertainment crown.

Bruce Forsyth was always willing to eskew steady comfortable success. Time and time again, he would walk out on a job others would kill for and rolled the dice just one more time. If he rolled 11 with two die, Bruce would roll again to try and get 12. The result of this attitude is that his career nearly sank without a trace on multiple occasions. But in the end, he had one of the longest, most enduring careers in British entertainment history. That was not because he had the most talent, but purely because he took those risks time and time again. Was he lucky? Certainly. Did he earn the right to get lucky? Absolutely.

Bruce Forsyth’s Big Night stands as one of the most remarkable, huge failures in British TV history. Yet strangely enough, it’s hard to do anything but admire it.

Thank you for reading.

The Windmill is still an imposing sight and continues to operate today as an all night cabaret club and up-market restaurant. The Windmill also lends it name to Great Windmill Street, a street I am extremely familiar with because I work there; The Red Consultancy has now been based at ‘GWS’ for nearly two decades.

To understand just how unflinchingly socially conservative British culture remained through this period, in 1959 a law was passed which made it illegal to publish literature classed as ‘obscene’. This became the legal battleground for the publication of DH Lawrence’s ‘Lady Chatterly’s Lover’, which led to the government taking Penguin to court over a book where an aristocratic woman in an unhappy and sexless marriage, starts flirting with and eventually has sex with her ‘lower class’ gamekeeper. It took just three hours for the jury in to decide that the book did not ‘deprave and corrupt’, kicking off a shift in societal attitudes that ushered in the ‘Swinging Sixties’.

That is, tits with nipple tassels attached of course; another regulatory requirement of the time.

Other comedians to hone their craft in the challenging environment of The Windmill include Peter Sellers, Spike Milligan, Barry Cryer, Tony Hancock and Tommy Cooper.

Trinder’s ‘catchphrase’ was ‘You Lucky People’, a catchphrase that seemingly has a Brucie ‘ring’ to it, but in fact, shows how Bruce built his presenting persona by happily borrowing and learning about ‘what worked’ from others, an approach that undoubtably enabled him to have such a long career.

BARB data on TV penetration begins in 1956, revealing 36% of UK homes had a TV. The year of Brucie’s big break (1958) marked the first year that more British homes had a TV than those that didn’t (51% to 49%). By 1962, three quarters of British homes would own a TV.

Quite incredibly, just three years later, Sunday Night at the Palladium was dead. ITV later admitted that cancelling Sunday Night was a huge mistake. The decision was driven by a growing concern around changing tastes and the emergence of more satirical and contemporary entertainment shows like The Frost Report (which would later spawn both Monty Python’s Flying Circus and The Two Ronnies). Whilst the cultural relevance of Sunday Night was undoubtably on a sharp decline in 1967 compared to it’s pomp just a few years before, it nonetheless remained a huge ratings. ITV killed it anyway. The show was brought back in 1973 by a wistful ITV leadership but it failed to replicate the same success and lasted just 15 episodes, compared to the nearly 400 episodes that aired between 1955 and 1967.

Indeed, even Julie Andrews career went into the doldrums, not helped by following up Star! with another flop Darling Lili in 1970 which lost even more money. The biggest female musical star of the 1960s was written off and barely appeared in any films at all in the 1970s as a result. Her career didn’t get back on track until 1979, when she picked up a Golden Globe nomination for Best Actress for her turn in 10, opposite Dudley Moore and Bo Derek.

One review called it ‘a variety show cum revue rather than any kind of structured musical’. Unfortunately, Bruce had created a show that would have probably been incredibly popular in the 1950s but was launching it just 18 months before the 1980s began. It was almost certainly a project doomed to fail from the off.

Re the sunbathing dancers: I suspect the coins used to "preserve their modesty" would have been pennies (slightly larger than the modern 2p).

Before decimalisation, a two pence coin was only part of UK coinage from 1797 to 1860. Admittedly, the original copper 2d coin would have provided better coverage as it was 41mm diameter, but its weight of two ounces might have become tiresome.

Great read Chris, ty!