Amstrad E-mailer (2000)

The story of how Alan Sugar launched the UK’s first smartphone - and why it failed so miserably.

The year 2000 was a year underscored with giddy optimism about the future of technology and its ability to build a better world. The internet had spent the last half a decade getting a foothold in the real-world (rather than just quietly existing on American military facilities and university campuses) and early start-up internet companies were the talk of Wall Street. Everyone knew that ‘online’ was the future and serious money was to be made by anyone who could grab a slice of the pie. With the ‘millennium bug’ already nothing more than a distant memory, Britain’s second most famous businessman at the time1 was finally ready to (re)enter the playing field. This is the story of Alan Sugar and the Amstrad E-mailer.

The Rise of Amstrad

For a generation of people, Alan Sugar is the man who has spent the last twenty years as the star of the UK version of The Apprentice. For another group, he was the loud, brash chairman of Tottenham Hotspur Football Club throughout the 1990s. For another even older cohort, he was a leading computing and technology entrepreneur in the 1980s. In other words, Sugar (previously Sir Alan, now Lord Sugar) has spent most of his life being talked about2.

After leaving school at 16, Alan Sugar got a job in the civil service, as a statistician for the Ministry of Education. This proper, white-collar job is a far cry from the ‘working class hero’ and market trader narrative Sugar has since weaved for himself. At 21 years old, Sugar used £100 of his own savings to create his own company. The name Amstrad stood for ‘Alan Michael Sugar Trading’ and the business plan was little more than Sugar selling dodgy car aerials out of the back of a white van.

He got his first proper break in the early 1970s in the somewhat unglamourous world of ‘Hi-Fi turntable lids’. By this point, hi-fi turntables (vinyl players) were perhaps the most popular consumer electronics item in the UK, but the price of the lids (needed to protect the unit when not in use) were high, driving the cost of each system up significantly. By creating hi-fi lids using a modern ‘injection moulding’ process rather than the standard andmuch slower ‘vacuum-forming’ method, Sugar could sell basic hi-fi systems at a price no-one else could compete with. By 1973, Amstrad was suddenly a proper electronics business.

Of course, it didn’t take too long for others to change their processes to remove Amstrad’s competitive advantage in the world of hi-fi’s. Alan’s response was to expand further into the world of audio, creating Amstrad branded amplifiers and tuners. This time, he achieved a competitive price by importing the products from the Far East, which at the time, was still a developing business practice.

The Amstrad CPC 464

In 1980 Amstrad was listed on the London Stock Exchange, making Sugar a proper cash millionaire for the first time. However, like many newly listed companies, Amstrad quickly started to suffer from analysts and investors asking questions about where future growth was going to come from. All their existing products were suffering from plateauing sales due to softer demand and increased imported competition, which also pushed his already thin profit margins to breaking point. This led to Sugar declaring ‘We need to move on and find another sector or product to bring us back to profit growth".

Sugar decided to follow the same rulebook as before; ‘don’t do it better - just do it cheaper’. In 1982, the Commodore 64 and Sinclair ZX Spectrum launched, kick-starting the home computing and gaming industry in the UK. Sugar’s relatively straightforward plan was to pivot out of audio and join the ‘British microprocessor boom’ by jumping on this new ‘home computing’ bandwagon.

The lead Amstrad engineer on the project (Ivor Spital) went out and bought a pile of almost every computer model available in the US and UK at the time to understand how they worked, what was important, and how much it might cost to replicate each element. The goal was to integrate all they key low cost-hardware elements into one package, which would retail as close to an ‘impulse buy’ price point as possible.

Less than two years later in 1984, the Amstrad CPC 464 was launched. Terrible name aside (the ‘CPC’ stood for Colour Personal Computer), the 464 was an ‘all-in-one’ system with connected monitor, keyboard and tape-deck. It also had 64k of RAM and had a joystick port, meaning you could easily turn it into a gaming machine. There was one very clear clear connection to what had gone before; a chunky, injection-moulded casing, but to meet to the brief of ‘not better, just cheaper’, compromises were everywhere. The CPC 464 even ran on it’s own unique software; a new Amstrad owned operating system called ‘AMSDOS’). Most tellingly, the monitor was extremely basic (technical name: a pixel VDU) which ran on BASIC 1.0; a programming language that quite amazingly, was already 20 years old (having been first created at Dartmouth College in 1964).

Despite its numerous flaws, the competitive price point and ‘something for everyone’ positioning meant the CPC 464 was a huge hit, selling more than 2 million units across Europe. Unlike many other computing kits at the time, it was also easy to use; essentially almost ‘plug and play’, at a time where many devices still required purchasers to undertake their own wiring, and sometimes even solder on their own plug. Two years later, Amstrad launched the PC1512 , which with a base model price point of £499, was one of the most affordable IBM ‘Office PC’ style machines yet, loaded with increasingly ‘must have’ features including a word processor, disc drive and printer. It was another success, capturing 25% of the European computer market.

I think, therefore I Amstrad

In 1986, Alan Sugar also purchased Sinclair Research for £5million, who just four years previously had kickstarted the whole British microprocessor boom with the launch of the ZX Spectrum. Since then, the ‘Sinclair Quantum Leap’ (which was targeted at a more upmarket and serious home user) was rushed to launch in 1984 and was beset by problems, including a rebuke from the Advertising Standards Authority for failing to meet customer orders. Building a product that did not appeal to existing Spectrum users turned out to be a significant strategic misstep by founder Clive Sinclair and he lacked the financial firepower to absorb losses. The final nail in the coffin was that the professional and business market had already started to shift towards the IBM PC platform, leaving hundreds of thousands of ‘Quantum Leaps’ pilled up in warehouses. In true ‘wheeler-dealer’ style Sugar quickly made back the £5million purchase price for the entire Sinclair Research business by flogging the excess Sinclair QL stock at an aggressive discount. In September 1986, the front cover of International Management ran with a picture of Sugar and the headline ‘The London street trader who would like to be as big as Sony’.

By 1988, the now FTSE100 listed Amstrad was poised to become a major player in the global computing boom that the 1990s would surely bring. With over 1,600 Amstrad staff across Europe, they had perfected a playbook of copying the best current product(s), stripping it back, building a budget friendly Amstrad clone, pricing competitively at ‘£something-99’ and then advertising aggressively on its affordability. Unfortunately, this race to the bottom eventually hit the ground with devastating force when the new PC2000 models came out of the factory with faulty hard-drives, leading to a very expensive product recall, a torrent of negative press, a collapse in order volume across the entire Amstrad PC range and a crisis of confidence in the Amstrad supply-chain. Before long, Amstrad had £325million worth of unsold stock, leading to speculation about inevitable price cuts and sales, which dampened demand even further.

“I was called to a meeting when it was revealed the PC2000 was crashing and nobody knew why. We had to decide to either recall them or bluff it out. The honest decision was to recall them and then everybody else in the market jumped on our heads and kicked us around and it really killed off Amstrad’s ambitions to be a big player in the grown-up PC market. We had a turnover of £1bn and profits of £116m. We had distributors in North America and the Far East. We were poised.”

Nick Hewer, Sugar’s Apprentice co-star and Director at Amstrad in 1986

Caught in a stock and cashflow death spiral, Sugar invested heavily in marketing to drive to drive demand back up, but this risky double down didn’t pay off. Backed into a corner, Sugar signed a deal with SKY to build and sell satellite equipment to power their pioneering new TV service. This decision was betrayal to the rival British Satellite Broadcasting service, which Sugar had previously supported; but he needed the cash. You can read more about that story (where Sugar is a small but important character) below...

Amstrad generated £107 million through selling SKY branded equipment in the first 12 months, stabilising and saving the business, which had been tipped by some to collapse. By 1990, Sugar was still the 70th richest man in Britain based on his £118 million stake in Amstrad, but this was down massively from a valuation of £590 million in 1988. Amstrad had fallen out of the big leagues, overtaken by others including IBM, Compaq and Apple, and would now have to settle to being a passenger, rather than a pioneer in the true computing boom that was to come.

Sugar, unwilling to give up the limelight, maintained his prominent media profile through his mouthy, opinionated role as chairman and part-owner of Tottenham Hotspur, which went through in 19913. However, whilst his media profile was arguably, bigger and hotter than ever, Amstrad were in the depths of cold despair after a string of failures. Two big hopes, the Amstrad GX4000 (a Sega Master System clone, launched in 1990) and the Amstrad Pen Pad (an Apple Newton clone, launched in 1993) both flopped. The business only remained solvent due to it’s steadily, profitable SKY partnership and in the later 1990s, this side of the business was split off and sold. By the turn of the millennium, what remained of Alan Sugar’s Amstrad had just 71 employees.

The Amstrad E-mailer

At the turn of the millennium Sugar’s shareholding in Spurs was put up for sale and he was increasingly desperate to trigger a 21st century revival for the small leftover rump of his Amstrad business. The company’s motto became ‘Always Innovating’ and more invention and creative thinking was encouraged. One long-serving Amstrad engineer called Bob Watkins started work on a new product concept to transform their small but growing footprint in the telephone market. However, the first boardroom-level pitch of the idea went badly, and Sugar named the project ‘BSI’ - ‘Bob’s Shit Idea’.

After further work and revisions, including reorientating the design to be built from an existing Amstrad model (a money-saving change which earned Sugar’s approval), the project started to be taken more seriously. The big idea was an internet connected home phone, with a large colour screen, with the ability to send emails, ‘surf the web’, send and receive videocalls and also access information that was increasingly being listed online, such as local cinema listings and bus timetables.

There was a significant gap in the market, with only one similar product having gone before; BT’s 1998 launch of the Easicom 1000. It was a bold attempt, with inbuilt buttons for ‘Mail’ and ‘Town Centre’ and ‘pull out QWERTY’ keyboard hinting at the future, but the basic dot matrix style screen and high price point (£179.99), meant it struggled. Sugar, always looking for shortcuts and cost savings, instructed his Amstrad executives to reach out to BT. The result was a joint venture; Amstrad would build the phones and BT would provide the required internet access.

This guaranteed internet access was critically important; although it is a little difficult to picture it now, back in the year 2000, email was the coolest modern consumer technology in the world. This was the era of Carrie Bradshaw in Sex in the City sat in her Manhattan apartment and using email for both work and pleasure; it was modern, aspirational, and unquestionably, the future. It is this cultural backdrop that ultimately led to the name for the new Amstrad ‘smart-home-phone’ becoming ‘The Em@iler’.

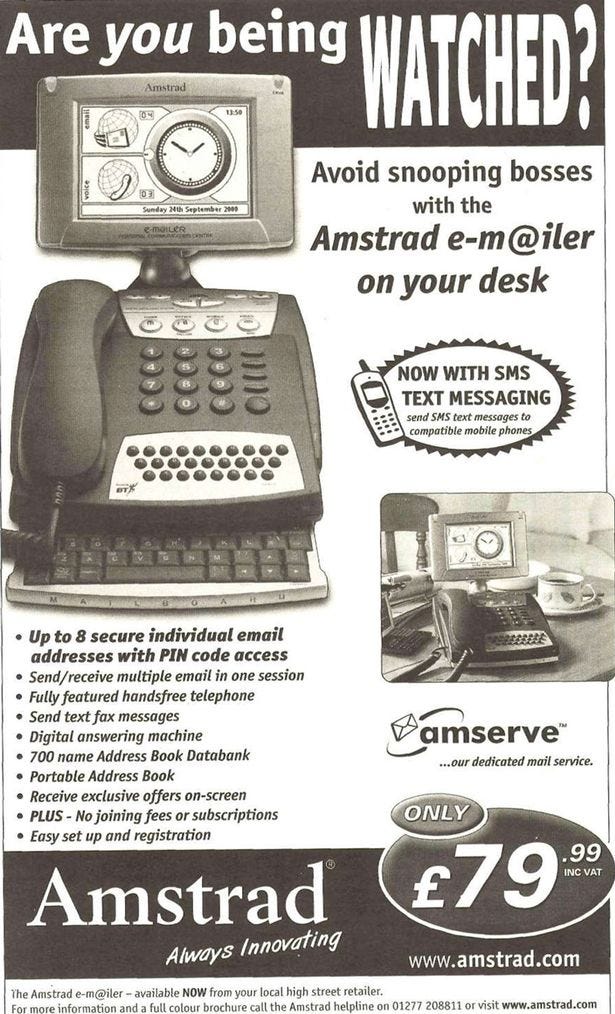

Other classic Amstrad compromises followed; the pull-out keyboard was built using the same design and layout as the original ZX Spectrum; the intellectual rights to which Sugar had bought back in the halcyon but distant days of the mid 1980s. Meanwhile, dreams of videocalls were ditched, with a camera being deemed too expensive to include, whilst the screen was downgraded to a ‘low bit colour LCD’ rather than the increasingly common and far superior ‘true colour LED’ screen. However, the price point for the Amstrad Em@iler at launch was a remarkably low £79.99. At a time when many families did not yet own PCs or computers (the cheapest of which would be at least £300-400), once again it seemed that by reducing the costs of entry to a new, desirable technology, Amstrad would have a sure-fire consumer technology hit on their hands.

Three Flaws

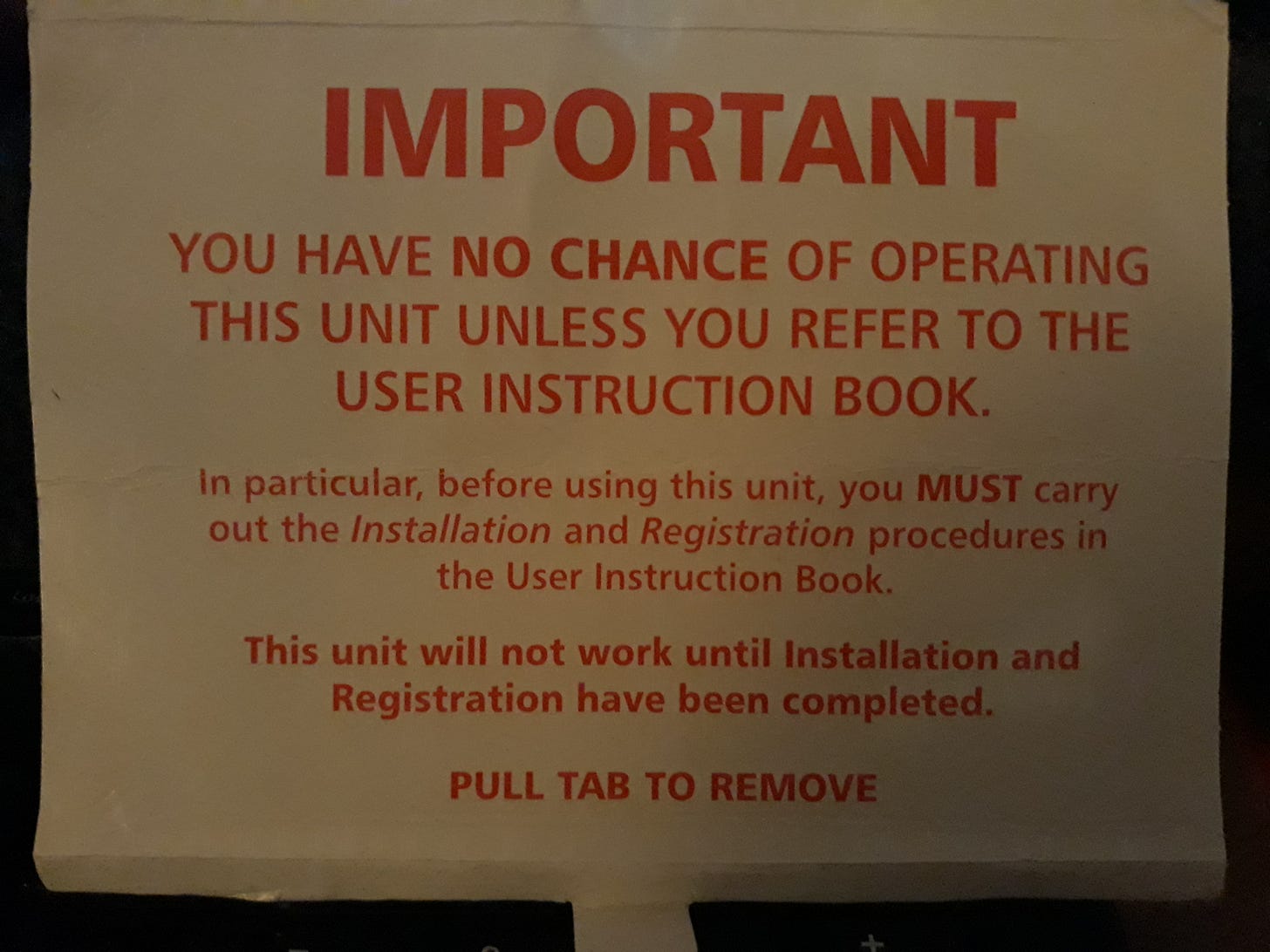

Unfortunately, there were three flaws with the Emailer, each of which was potentially fatal in its own right. The first was the lack of user-friendly design. Back in the early 1980s, Amstrad was primarily selling CPC 464s and PC1512s to technology geeks and early adopters. Among that audience it was widely understood that there would be a steep learning curve and plenty of non-intuitive moments to navigate as a user of any piece of hardware or software. By 2000, the world had changed; Windows 95 was the ‘great leap forward’ for user experience, and programs like Internet Explorer made it easier than ever to ‘surf the web’. Expectations had shifted and technology providers were now expected to make it easy for you. Meanwhile, customers unboxing their new Amstrad Emailer were met with this.

The second problem was the advertising. The TV advert featured a man in a garish Union Jack suit, claiming ‘Britain Needs You!’… to buy an internet connected phone, I suppose (!?). Meanwhile print adverts claimed ‘Are you being watched’, stating that the Em@iler could sit on your work desk to help you ‘avoid snooping bosses’4. Yeah, me neither. It seemed Sugar and Amstrad didn’t really understand the product or the target market at all and marketing straplines like ‘Getting Britain Emailing!' made it sound more like a New Labour government initiative than an aspirational, modern piece of technology.

The third, and undoubtably biggest flaw was the small print. The very competitive price of £79.99 meant that Amstrad actually made a loss on every single unit sold. But once you set-up your email on the device, the machine would check for new emails every morning, by sending a request to the mail server, through the BT network. This put a small charge on your phone bill; with the money being split between Amstrad and BT. Unfortunately, the small charge wasn’t that small; the monthly cost for checking your emails (which the Emailer did automatically, relying on small print rather than asking explicit permission) was an eye-watering £6.20 a month. This essentially meant that after 12 months, you had bought the phone again.

In another attempt to claw back some of the costs of production, the device had another innovative solution; when not in use, the 'always on' screen would display advertising5. Users could pay a one-off £15 fee to remove this, which left another sour taste in the mouth of purchasers. On top of this, ‘surfing the web’ was charged at 5p per minute, whilst sending an SMS to a mobile device was 50p per message6. With all the hidden charges, the Amstrad Emailer quickly pick up a terrible reputation for creating 'bill shock' and being ‘anti-user’. Others said buying one was tantamount to inviting a parasite into your home.

Aftermath

Despite terrible press and poor sales of just 110,000 units, Amstrad didn’t give up on the Emailer. They were right that there was something in the product and at that time, it offered functionalities and opportunities to users that were otherwise unavailable. Sugar also saw potential greatness in building an advertising network using the devices that were ‘prominently displayed in the home’ to create ‘hundreds of thousands of in-home digital billboards’. The company also started putting up digital screens across the UK in petrol stations and other locations, under the spin-off ‘Amscreen’ name.

For round two, Sugar ditched the partnership with BT, enabling them to lower some of the charges (slightly) and they also upgraded the screen. The new ‘Amstrad E2 E-Mailer Plus’ was launched in 2002 at £99.99 with a killer feature; you could now play over 40 iconic ZX Spectrum games such as Jet Set Willy on the device. However, once again, the small print was a disgrace. Despite the ZX Spectrum games library being 20 years old (and fully owned by Amstrad), they decide to make it impossible to actually buy games on the device. Users could only ‘rent’ them, at a cost of 50p for 4 days. This is one of the earliest examples of a games subscription model in action, long before the rise of the XBOX Game Pass. In reality, the game would fully download to the device as if purchased, before being forcibly deleted four days later.

The new ‘E2’ model also included a card reader; designed to kick start the e-commerce and online shopping revolution by turning your home phone into an online check-out till (with Amstrad poised to take a cut, in much the same way that providers like Stripe do today). But in 2002, online retail was nowhere near ready to give people a good online shopping experience and the entire function proved to be a damp squib.

A final swing of the bat came in 2004, with a new ‘E3’ model with a much-improved screen and a separate gaming pad (in the style of a Playstation controller). This device also finally offered videocalls. But by now, PC and laptop prices were falling to record lows, whilst mobile phones were also slowly getting smarter. Most UK mobiles now had access to 2G or WAP internet services; slow, limited and expensive - but on a portable device. At this point, the Emailer was offering the same slow, limited and expensive online service, but on a home phone. If the portability didn’t matter, you could now get an entry level PC for just twice the price of the new E2/E3 models. In other words, the viability of the entire endeavour was gone.

As a piece of hardware, the Emailer was ostensibly a ‘static smartphone’ that was half a decade ahead of the arrival of the iPhone. It was full of interesting, innovative ideas that were along the right lines but none of it really worked or gave a good user experience. Across the three models over 450,000 Emailer devices were sold in the UK (a not insignificant number). However, every unit was sold at a loss, and the vast majority were either never registered for email or deliberatly had the ‘expensive’ server access disabled in the settings. Somehow, Amstrad had managed to create and launch a product that made it prohibitive to do the one thing the product was designed to do and was named after. It would be ironic, if only the terrible decisions regarding billing and charges that led to this point were anything other than entirely deliberate; Sugar himself went on record stating “I wanted to get into a business where I was no longer on the treadmill of expecting to make a profit on hardware”.

The Emailer essentially finished of what was left of Amstrad. Significant losses were posted in 2001 due to the losses incurred on every Emailer sold. Bob Watkins was the man with a ‘shit idea’ again, and he was forced to resign after 25 years at the company. Anything left of the business was then sold in 2007 to long-time collaborators BSKYB, as Sugar pivoted into being a full-time media celebrity on the back of the roaring success of the BBC series The Apprentice. He later claimed that the Emailer “just about broke even in the end”, although even this result remains a disaster for the product line that was supposed to entirely rejuvenate the company.

In June 2011, BSKYB, who had ended up owning the servers for the Emailer following the sale of the business, shut down the network, instantly bricking the estimated 150,000 Emailers still in use and rendering them able to only make and recieve basic landline calls. At that point, the UK’s very first smart-phone finally became what everyone thought it was all along; totally dumb.

Thank you for reading - please ‘like’ it if you liked it!

Richard Branson unarguably takes the number one position, especially as at the time he had recently appeared in an episode of the biggest TV show on the planet; F.R.I.E.N.D.S..

If you happen to follow him on Twitter, you’ll quickly realise that having people talking about him is something Alan Sugar needs, rather than endures.

Sugar seemed to actively court controversy as Spurs chairmman, ending up at the High Court in 1993 over a falling out with manager Terry Venables. Tottenham star player Teddy Sheringham also fell out with him. After secuing a £3.5million transfer to Manchester United in 1997, Sheringham claimed that Sugar had rung him, warning him “If I read any s**t about the club in the papers, I'll be after you - I'll hound you and get my own back”. Sheringham also accused Sugar of being ‘a miser’ when it came to funding transfers and wages for the players Spurs needed to compete.

This 'subsidising' model has since been made mainstream by Amazon and it's Fire devices

SMS, like email, was also becoming massively popular and desirable. But rather than make this another great accessibility feature, they decided to make it incredibly expensive. The desire to make money constantly got in the way of delivering a user-friendly product.

I think the UK’s first smart phone was the ICL Open Per Desk (OPD) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One_Per_Desk which pre-dates the Amstrad product by 16 years.

A mention of https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viglen is probably deserved: they were bought by Amstrad in 1994 and sold to Westcoast/XMA in 2014.